The Trillion-Dollar Depreciation Gamble

How Debt-Financed AI Infrastructure, GPU Collateral, and Aggressive Accounting Collide

Michael Burry’s November 2025 accusation that Big Tech is perpetrating “one of the more common frauds of the modern era” through server depreciation manipulation has collided with an even more concerning development: the emergence of a $125+ billion debt-financed AI infrastructure boom that makes the telecom bubble’s financing arrangements look conservative by comparison.

This analysis examines the intersection of three critical trends: hyperscaler depreciation schedule extensions that have added $13+ billion in artificial annual earnings, a surge in GPU-collateralized debt financing that now exceeds $20 billion, and Oracle’s unprecedented $108 billion debt load as the company races to fulfill a $300 billion contract with an unprofitable customer (OpenAI). The implications extend beyond individual company risk to systemic concerns about asset-backed securities, private credit markets, and the fundamental economics of AI infrastructure.

Part I: The Depreciation Manipulation Case

What the Hyperscalers Actually Changed

The depreciation schedule extensions are documented fact. Between 2020 and 2025, all four major hyperscalers systematically extended server useful lives from industry-standard 3-4 years to 5-6 years, generating $13+ billion in cumulative annual earnings benefits.

Microsoft moved first in July 2020, extending server lives from 3 to 4 years, then jumped to 6 years in July 2022. The FY2023 impact: $3.7 billion in additional operating income. Microsoft’s depreciation rate as a percentage of net property and equipment fell from 30-34% in FY2014-2020 to approximately 15% by FY2024.

Google followed suit, extending server lives from 3 to 4 years in January 2021, then to 6 years in January 2023. The 2023 change alone reduced depreciation expense by $3.9 billion and boosted net income by $3.0 billion.

Amazon pioneered the trend, moving from 3 to 4 years in January 2020, then to 5 years for servers and 6 years for networking equipment by 2022. But Amazon’s February 2025 decision to reverse the extension for AI-specific servers-shortening useful life from 6 back to 5 years-represents the most significant validation of Burry’s concerns. The company cited “increased pace of technology development, particularly in the area of artificial intelligence.”

Meta extended non-AI server lives to 5.5 years in January 2025, projecting $2.9 billion in reduced depreciation expense. Notably, Meta explicitly excluded AI servers from the extension-an implicit acknowledgment that GPU-intensive infrastructure depreciates faster than traditional compute.

The Technical Case for Accelerated Obsolescence

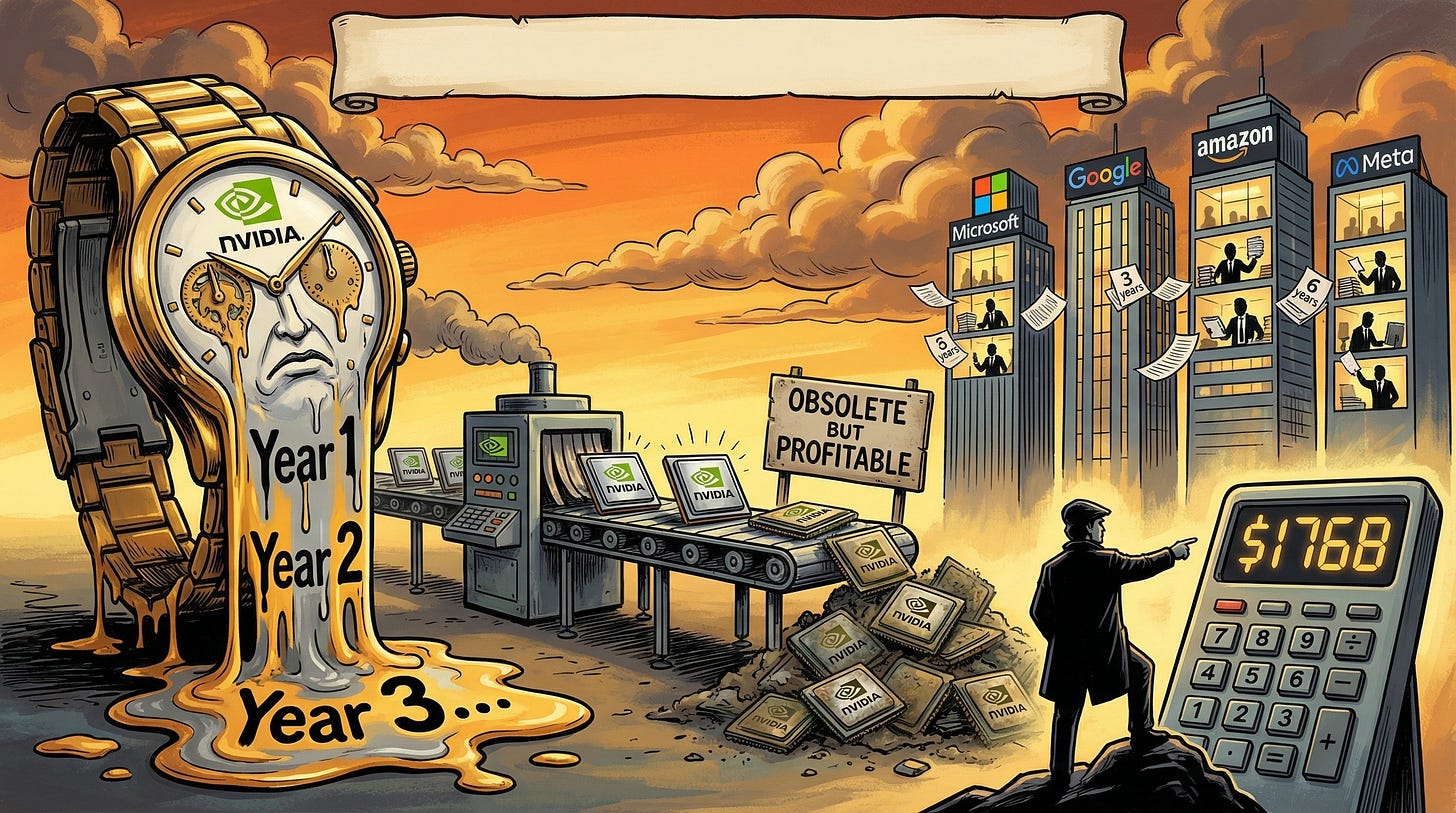

Burry’s core argument rests on a fundamental mismatch: NVIDIA releases new GPU architectures annually (accelerated from 18-24 month cycles), yet hyperscalers depreciate these assets over 5-6 years. The technical evidence supports his concern.

A Google architect’s assessment found GPUs running at 60-70% utilization-standard for AI workloads-survive only 1-3 years due to thermal and electrical stress. Princeton’s CITP analysis of Meta’s Llama 3 training study documented a 9% annualized GPU failure rate, implying 27% failure over three years. H100 GPUs consuming 700 watts per chip create significant thermal degradation that legacy servers never faced.

Technological obsolescence compounds physical degradation. NVIDIA’s GB200 “Blackwell” chip delivers 4-5x faster inference than the H100. CEO Jensen Huang stated: “When Blackwell starts shipping in volume, you couldn’t give Hoppers away.” NVIDIA declared the A100 series end-of-life in February 2024, merely four years after its 2020 release.

Part II: The Debt-Financed Infrastructure Boom

The Scale of AI Infrastructure Debt

A UBS report from November 2025 revealed that AI data center and project financing deals surged to $125 billion in 2025, up from just $15 billion in the same period in 2024-an 8x increase. Morgan Stanley estimates private credit markets could supply over half the $1.5 trillion needed for data center buildout through 2028. JP Morgan now estimates AI-linked companies account for 14% of its investment grade index, surpassing U.S. banks as the dominant sector.

The financing has taken multiple forms: investment-grade corporate bonds (Meta’s $30 billion, Oracle’s $18 billion), private credit facilities (Meta’s $29 billion deal with PIMCO and Blue Owl), GPU-collateralized debt (CoreWeave’s $9.9 billion), and an emerging asset-backed securities market that BofA estimates could add $50-60 billion in supply in 2026.

Oracle: The $108 Billion Test Case

Oracle has emerged as the most extreme example of debt-financed AI infrastructure ambition. As of December 2025, the company carries approximately $108 billion in debt-up from $92.6 billion in May-making it the largest issuer of investment-grade debt among non-financial firms.

The debt is being deployed to fulfill a staggering $300 billion, five-year contract with OpenAI for cloud compute services, with payments expected to reach $60 billion annually starting in 2027. Oracle’s remaining performance obligations have exploded to $523 billion-up 438% year-over-year-as the company has signed deals with OpenAI, Meta, NVIDIA, xAI, and others.

The December 2025 Warning Signs: Oracle’s fiscal Q2 2026 earnings (reported December 10, 2025) revealed concerning dynamics. Revenue of $16.06 billion missed expectations of $16.21 billion. Free cash flow was negative $10 billion for the quarter-nearly double the consensus estimate of negative $5.2 billion. The company raised its full-year capex guidance to $50 billion, up from $35 billion just three months prior. The stock fell 11% after the report.

Citi analyst Tyler Radke estimates Oracle will need to raise $20-30 billion in debt annually for the next three years. Moody’s changed its outlook on Oracle to negative in July 2025, citing “the expectation of continuing elevated leverage and increasingly negative free cash flow.” Oracle’s 5-year credit default swaps have climbed to their highest level since 2009.

The Counterparty Problem: The most significant risk may be Oracle’s largest customer. OpenAI remains unprofitable and relies on continuous funding rounds. Sam Altman has stated OpenAI will reach $20 billion in annualized revenue in 2025 and projects “hundreds of billions” by 2030-but paying Oracle $60 billion annually starting 2027 requires extraordinary revenue growth. As Moody’s analysts noted: “Given the lack of financial information about the potential counter parties, this risk assessment is subjective at best.”

The $38 Billion Stargate Debt Package

In October 2025, banks led by JPMorgan Chase and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group began marketing a $38 billion debt offering-the largest AI infrastructure financing in history-to fund data centers tied to Oracle. The package is split across two facilities: $23.25 billion for a Texas campus and $14.75 billion for a Wisconsin project.

These facilities are part of the Stargate initiative, a $500 billion AI infrastructure project announced by President Trump in January 2025 involving OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank. The project aims to build 10 gigawatts of compute capacity across sites in Texas, New Mexico, Ohio, and Wisconsin. SoftBank has already borrowed $10 billion from Mizuho for its portion; Blue Owl raised $18 billion from Japanese banks for a New Mexico site.

The financing structure reveals the precarious nature of this buildout. Oracle has signed 17-year leases on sites to support the debt, with lenders stepping in to assume control if projects default. The dependency chain is stark: Oracle borrows to build infrastructure → OpenAI commits to pay Oracle → OpenAI must raise funds or generate revenue → investors must continue believing in the AI thesis.

CoreWeave: The GPU Collateral Experiment

CoreWeave has pioneered a novel and concerning financing model: using NVIDIA GPUs as collateral for massive debt facilities. The company has raised $25+ billion in total capital commitments, with approximately $9 billion in current and non-current debt secured primarily by its GPU inventory.

The Collateral Problem: Unlike real estate-which generally appreciates and can be amortized over decades-GPUs are rapidly depreciating assets. CoreWeave’s loan terms require quarterly payments based on cash flow and, critically, the depreciated value of the GPUs used as collateral. As new NVIDIA architectures launch and GPU rental prices fall, the collateral value shrinks while the principal remains fixed.

The H100 rental market has already seen dramatic price declines: from $8/hour at peak to $2.36-3.50/hour by late 2025-a 60-70% reduction. Analysis suggests that once H100 rental rates fall below $1.65/hour, revenues no longer recoup the investment. Prices need to remain above $2.85/hour to beat stock market returns.

The Depreciation Discrepancy: CoreWeave depreciates its GPUs over 6 years-the same aggressive schedule the hyperscalers use. Competitor Nebius uses a 4-year depreciation period. This longer schedule artificially suppresses CoreWeave’s operating expenses and inflates its operating income, while masking the true rate of asset value erosion.

Jim Chanos, the legendary short-seller who exposed Enron, has raised concerns about CoreWeave’s model. The company’s annualized interest expense of approximately $1.2 billion approaches its adjusted EBITDA of $3.4 billion, leaving minimal margin for GPU depreciation. CoreWeave’s stock has fallen approximately 57% from its June 2025 high, though it recovered after announcing a $14.2 billion contract with Meta.

Customer Concentration Risk: Just two companies drove 77% of CoreWeave’s 2024 revenues, with Microsoft accounting for 62%. These largest customers are also its biggest competitors-hyperscalers who could decide to build rather than rent at any moment.

The GPU-Backed Debt Contagion

CoreWeave’s model has spawned imitators. London-based Fluidstack secured over $10 billion in loans from Macquarie and other lenders using NVIDIA GPUs as collateral. Multiple AI cloud computing startups now use high-power chips as collateral, with total GPU-backed borrowing exceeding $20 billion.

Lenders are demanding interest rates in the double digits-exceeding most high-yield bond requirements-reflecting the depreciation risk. Some companies are exploring AMD chips as alternative collateral. TensorWave is actively seeking debt financing with AMD chips as collateral, which would be one of the first such deals.

The fundamental question remains: what happens when the next NVIDIA architecture launches and existing GPU collateral loses 40-50% of its value overnight? The loans require principal payments; the collateral doesn’t maintain principal value.

Part III: The Securitization Parallel

Data Center ABS and CMBS: 2008 Redux?

Asset-backed securities (ABS) and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) are emerging as significant funding sources for AI infrastructure. BofA notes that digital infrastructure-primarily data centers-accounts for $82 billion of the $1.6 trillion U.S. ABS market, having expanded more than 9x in less than five years. Data centers backed 63% of that digital infrastructure segment.

These securities bundle data center lease payments-rent paid by hyperscalers to facility operators-into tradeable bonds structured by risk tranche. The pitch is compelling: hyperscaler tenants have strong credit ratings, long-term leases, and mission-critical need for the facilities.

The 2008 Echo: ABS are viewed with caution since the 2008 financial crisis, when billions of dollars’ worth of products turned out to be backed by soured loans and highly illiquid assets. The data center version differs in that the underlying cash flows come from creditworthy tenants rather than subprime borrowers. However, the structures share a common vulnerability: they assume the underlying asset-whether a house or a GPU cluster-maintains value throughout the security’s life.

Al Cattermole, fixed income portfolio manager at Mirabaud Asset Management, told Reuters in November 2025 that his team had not invested in any AI-linked investment-grade or high-yield bonds. His reasoning: “Until we see data centres being delivered on time and on budget and providing the computing power that they are intended to-and there still being the demand for it-it is untested. And because it’s untested, that’s why I think you need to be compensated like an equity investor.”

Private Credit: The New Risk Reservoir

Private credit has become a crucial funding source for AI infrastructure. UBS estimates private credit AI-related loans nearly doubled in the 12 months through early 2025. Morgan Stanley projects private credit could supply over half the $1.5 trillion needed for data center buildout through 2028-approximately $750 billion.

The appeal for borrowers is clear: private credit offers fixed-rate structures, customized terms, and avoidance of public bond market scrutiny. Meta’s $29 billion deal with PIMCO and Blue Owl-structured as $26 billion in debt and $3 billion in equity-exemplifies the model. Microsoft struck a $30 billion partnership with BlackRock. xAI raised $5 billion in syndicated debt.

The Illiquidity Risk: Unlike traded bonds, private credit loans are harder to trade during market turmoil. The Bank of England has flagged that “pockets of risk are building in parts of the financial system populated by opaque, hard-to-trade illiquid assets.” If AI demand disappoints and borrowers struggle, private credit investors may find themselves holding assets with no market and rapidly deteriorating collateral.

Part IV: Historical Parallels and Differences

The Telecom Bubble Comparison

The telecom bubble offers the most relevant precedent. WorldCom’s $11 billion fraud included depreciation manipulation alongside capitalizing operating expenses. Waste Management stretched garbage truck depreciation periods to reduce annual expense, ultimately restating $1.7 billion in earnings.

More broadly, $500+ billion was invested in fiber optic infrastructure, 85-95% of which remained “dark” (unused) four years after the bubble burst. Global Crossing achieved a $47 billion market cap without ever turning a profit. Lucent Technologies offered $8.1 billion in vendor financing-about 24% of revenue-and collapsed when customers defaulted.

JP Morgan has explicitly made this comparison, estimating AI will need $650-800 billion in annual revenue by 2030 just to generate a 10% return on infrastructure capex. Bain estimates an $800 billion annual revenue gap between AI investment and revenues.

Critical Differences

Several factors distinguish the current situation from the telecom bubble. Hyperscalers possess massive cash reserves and sustainable core businesses unlike pure-play telecoms. Amazon’s AWS, Microsoft’s Azure, and Google Cloud generate hundreds of billions in annual revenue with strong operating margins. The AI infrastructure spending, while enormous, represents a fraction of their financial capacity. Meta issued its first dividend in 2024 despite the capex boom-impossible for debt-laden 1990s telecoms.

Additionally, infrastructure financing has matured as an asset class. Specialized lenders understand data center economics. Structures include ring-fenced cash flows, specific covenants, and security packages that didn’t exist in the 1990s.

However: Oracle is not a hyperscaler. It carries $108 billion in debt, has negative free cash flow, and is building capacity for a customer that has never been profitable. CoreWeave is not a hyperscaler. It has 77% customer concentration, GPU collateral that depreciates rapidly, and an interest coverage ratio of 0.17. The startups borrowing billions against GPU inventory are certainly not hyperscalers. The comparison to telecom overbuild is most apt not for Microsoft or Google, but for the second and third tier of infrastructure providers.

Part V: The NVIDIA Paradox

Why Obsolescence Might Benefit NVIDIA

Here’s where Burry’s thesis creates an unexpected implication for NVIDIA investors. If GPUs depreciate faster than accounting schedules suggest, this creates sustained demand for replacement chips rather than a one-time buildout.

CoreWeave CEO Michael Intrator provided direct evidence: “A batch of Nvidia H100 chips became available because a contract expired, and they were immediately booked at 95% of their original price.” He added that “all of our Nvidia A100 chips, which were announced in 2020, are all fully booked.”

The “value cascade” model explains how older GPUs retain economic utility despite obsolescence: Years 1-2 for frontier model training, Years 3-4 for high-value real-time inference, Years 5-6 for batch inference and analytics. Meta exemplifies this tiering-training on cutting-edge H100/H200 GPUs but running inference on AMD MI300X chips.

If Burry is correct that 6-year depreciation is aggressive, the implication is that hyperscalers must continuously purchase new NVIDIA chips at 3-4 year intervals rather than 6-year cycles. This doubles the replacement frequency and sustains demand indefinitely. NVIDIA’s $500 billion backlog through 2026 supports this thesis.

The Competitive Moat

NVIDIA’s defensive position remains formidable regardless of the depreciation debate. SemiAnalysis conducted a five-month benchmark of AMD’s MI300X in December 2024 and concluded: “For all models, the H100/H200 wins relative to MI300X. AMD’s software experience is riddled with bugs rendering out of the box training with AMD impossible... The CUDA moat has yet to be crossed by AMD.”

NVIDIA’s CUDA ecosystem encompasses 3.5 million developers with nearly two decades of optimization. Intel’s Gaudi holds less than 1% market share. Custom silicon from Google, Amazon, and Meta handles primarily inference and internal workloads-less than 20% of frontier model training runs on non-NVIDIA silicon.

Conclusion: Layers of Risk

The AI infrastructure financing landscape presents layered risks that compound upon each other:

Layer 1 - Depreciation Manipulation: Hyperscalers have documented $13+ billion in annual earnings benefits from extending depreciation schedules. Amazon’s reversal for AI servers validates that these schedules are aggressive.

Layer 2 - Debt Financing Surge: AI infrastructure financing surged to $125 billion in 2025 (8x 2024 levels), with projections of $750 billion in private credit through 2028. This creates massive leverage exposure if demand disappoints.

Layer 3 - Collateral Degradation: GPU-backed debt exceeding $20 billion depends on assets that have already declined 60-70% in rental value. The 6-year depreciation schedules used by borrowers like CoreWeave mask this reality.

Layer 4 - Counterparty Concentration: Oracle’s largest customer is unprofitable. CoreWeave’s two largest customers represent 77% of revenue. The dependency chains are fragile.

Layer 5 - Securitization Proliferation: Data center ABS/CMBS have grown 9x in five years. Private credit markets are increasingly exposed to AI infrastructure. The lack of transparency about actual utilization and demand echoes pre-2008 mortgage market opacity.

The key variable is whether AI generates sufficient return on investment to justify the infrastructure buildout. Combined hyperscaler capex guidance exceeds $300 billion for 2025 alone. Backlogs total $747 billion. Power constraints, not demand, appear to be the limiting factor.

For NVIDIA, the paradox of obsolescence remains intact: even if individual GPUs become worthless faster than accounting suggests, the aggregate effect is a treadmill that customers cannot exit. Oracle’s $50 billion annual capex, CoreWeave’s refinancing requirements, and the broader infrastructure boom all translate to continuous GPU orders.

The risk is not that AI demand disappears-it almost certainly won’t. The risk is that the second and third tier of infrastructure providers, loaded with debt secured by depreciating assets, cannot survive the gap between infrastructure investment and AI monetization. Amazon’s depreciation reversal may represent the market’s most honest signal: AI hardware depreciates faster than traditional servers, but the hyperscalers will keep buying. Whether Oracle, CoreWeave, and the GPU-backed lending ecosystem can say the same is the $176 billion question.